Most people are familiar with mutual funds because they’ve been around longer and are available in everyone’s 401K’s. Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are similar to mutual funds but have powerful advantages.

Mutual funds and ETFs

They both invest in an underlying group of securities that offer easy diversification. You only need to own a few funds for complete diversification because each fund owns dozens, or even hundreds, of individual holdings. They can be broad-based like a total stock index or specialized, only focusing on biotech, small cap growth, or even a specific country.

All in all, mutual funds and ETFs serve the same purpose in your investment strategy. So why would you choose one over the other? ETFs have some advantages your average investor either takes for granted or doesn’t know about.

An obvious difference between the two types of investments is how they are bought and sold.

Mutual funds trade at the end of the day. The fund managers see how much all of their assets are worth (Net Asset Value), and then create or redeem shares based on investors buying or selling the shares in their accounts. You will always pay or receive whatever the mutual fund’s NAV is at the end of the day.

ETFs trade throughout the day. They use ‘market makers’ and ‘authorized participants’ to keep their NAV and price closely linked. If price deviates too far from the NAV, they will step in to close that gap. The market makers make money doing that so they are happy to provide the service.

That little difference in how they trade leads to almost all of the advantages exchange traded funds have over mutual funds.

Why are ETFs better?

ETFs trade throughout the day.

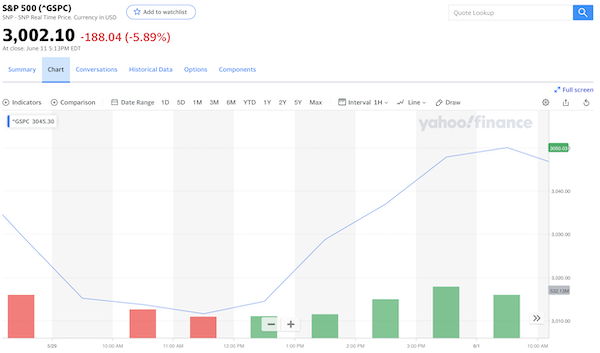

That means you know how it’s performing and can buy or sell it right then. Look at the chart of 5/29/2020 as an example. The market is depressed for the first half of the day. Plenty of time to buy an ETF, and then profit when the S&P 500 went up the second half of the day.

If you had purchased a mutual fund, it would have been bought at the end of the day when it’s NAV was higher.

ETFs have lower costs.

ETFs wrap all of their expenses into one fee, the management fee. For a typical passively-managed ETF, that fee will be in the neighborhood of 0.15%. The more specialized the ETF is, the more its management fee will be. A sector fund might have a 0.80% fee on the high end so be careful with those. Since ETFs trade on the exchanges you may have to pay a commission when you buy or sell. Commissions are going away as Schwab, TD Ameritrade, and Fidelity fight it out, though.

Mutual Funds can have front-end loads where they literally take 5-8% of the money you initially invest. You give them $10,000 and only $9,200 gets invested. They can have back-end loads where they charge an extra percentage when you sell the fund. They have 12b-1 fees. That’s where you are paying for their marketing efforts. And then you have the management fee. For a passively-managed mutual fund, the management fee will be reasonable, but that’s on top of the other fees I’ve mentioned. A lot of mutual funds are actively managed, and those managers want to get paid! It’s very common to see management fees above 1% for actively managed mutual funds. Again, that’s on top of the other fees.

Pro tip: A front-end load depresses your returns the entire time you own the fund. Here’s how: let’s say a fund earns 20% in one year. You earn 20% on the $9,200 that was invested, or $1,840. But you gave the fund company $10,000. The $1,840 return is only 18.4% on the amount you gave them. And that will continue to happen every year you own the fund. You’ll never catch up to the returns the fund is saying it earned.

ETFs don’t have multiple share classes.

If you are looking to purchase the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust, there’s only one. Its ticker symbol is SPY. It’s very easy to look up and keep track of.

If you are looking to purchase an S&P 500 mutual fund, you may see class A, class B, class C, investor class, admiral class, class r6, and on and on. What are those different classes? They are different fee structures! Some are much more expensive than others. Some are cheaper if you plan on holding long-term while another class type could be better if you make a quick move. Why would they have the same fund available with so many fee structures? Because they want your money. They hope you pick the wrong one and increase their fees. If you have to use mutual funds at least educate yourself on the different share classes.

They also use the different classes for marketing. If you own admiral shares at Vanguard, then you must be rich and they’re going to send extra marketing materials to you!

ETFs are more tax efficient.

Most ETFs don’t pass on any capital gains to the investor. It’s a little complicated how they get around this. I’ll go into more detail later in the article.

Meanwhile, mutual funds pass along capital gains, but not capital losses. The losses will stay in the fund to offset future gains. They don’t completely disappear but there’s no immediate benefit for the investor. Mutual funds also suffer from ‘cash drag’, which will be explained later.

As a long-term investor, holding funds for several years, would you rather:

- Not pay any taxes each year, and only pay taxes once you sell the fund (and you’ll know exactly what your tax bill will be), or

- Pay some taxes each year, never really knowing how much it’ll be, and then pay taxes again when you sell the fund several years later.

#1 is a clear winner to me. That’s an ETF. #2 is a mutual fund.

Your fellow mutual fund investors affect your performance!

Mutual funds create capital gains through 1) regular fund manager actions like trading securities, or… 2) other investors’ actions! Yes, other investors can affect the amount of capital gains you pay! If investors pile on the redemptions, the fund will be forced to sell securities, which affects you. (The previous link requires a free registration with Morningstar but it’s well worth the read.)

To avoid this, mutual fund managers will keep cash on hand to cover redemptions without having to sell. During normal times this works, but when SHTF and everyone is panicking, they won’t have the cash on hand to cover the redemptions and will be forced to sell underlying securities at the worst possible time.

The cash on hand to fix that problem leads to another disadvantage: a permanent cash drag. Let’s say we have an ETF and a mutual fund that both track the S&P 500. Their performance and fees are exactly equal. The only difference is that 1% of the mutual fund is in cash and 99% is invested in the S&P 500 versus the ETF being 100% invested in the S&P 500. That cash is a permanent 1% drag on performance versus the ETF. I don’t mean the ETF returns 9% and the mutual fund returns 8%. The difference is much smaller; it would be 1% of the 9%. So the mutual fund would return 8.91%. It doesn’t seem like much of a difference, but it will always be there, compounding year after year. Why sign up for that?

How do ETFs avoid passing along taxes?

How does the ETF wrapper avoid those two issues? By using something called Authorized Participants (big investment firms that will trade the underlying securities in large volumes). AP’s take part in unit creation and redemptions. When you sell shares of an ETF, it’s not the fund itself giving you the cash. The cash comes from the AP if need be.

On the other side of the transaction, the ETF can trade securities in-kind with the AP so no capital gains are realized by the fund. In-kind transfers are when shares of stock move between parties. There’s no sale or purchase being converted to cash, and therefore no tax liability.

I’m not really sure why this tax loophole is allowed so don’t be surprised if it disappears at some point. Section 852(b)(6) of the tax code is the rule being exploited. Its original intent was to allow open-end mutual funds to deliver shares of underlying stock in lieu of cash during a market panic. As long as it is allowed, though, why wouldn’t you want to take advantage of it?

What to look out for when purchasing or selling ETFs

If ETFs have one weakness, it’s this: if there is a major liquidity crisis, those same market makers and authorized participants could disappear and that would wreak havoc on the ETF markets (free registration). Prices would disconnect from NAV, and the gap would only widen as liquidity worsened. After all, the market makers aren’t required to trade. They only do it when they can take advantage of inefficiencies. During normal times, the ETF with ticker symbol SPY will have a 1 cent bid-ask spread while a new ETF could have a 10 cent spread. During turbulent times, all ETFs could have 10 cent or higher spreads. That’s why you should always use limit orders on trades when things are turbulent.

Why do newer and/or smaller ETFs have larger spreads even during normal times? That’s because the market makers aren’t watching them as closely as the big ETFs. They also may not be ready to participate in a new ETF’s trading.

Take a look at the chart below as a lesson on using limit orders. An individual investor entered a market order for the ETF SWAN on 3/18/2020. If I remember correctly, the trader was buying 7,000 shares. It’s not a heavily traded security, so his order soaked up all of the regular volume at the current prevailing price in the $26-$27 range. A predatory market maker then swooped in to satisfy the last 700 shares. They jacked the price up by about 15% on the last shares of that order. They did their job by making sure there was liquidity but they did it at a ridiculously high level. The investor could have protected himself with a limit order. I’m sure he would’ve been happy with 6,300 shares bought at $27 and skipped having those final 700 shares filled at almost $31!

Again, that entire weakness can be avoided by using limit orders during high-volatility times. Or better yet: don’t sell during market panics!

ETFs are superior to open-end mutual funds in several respects. If you have no way of avoiding mutual funds, like your 401K only offers mutual funds, then make sure to pick low-cost funds. The best choice will usually be to pick the 3 fund portfolio.