Closed-end funds can give your retirement income a boost through managed distributions in an environment where the fund managers can stick to long-term strategies. This ultimate guide to closed-end funds provides all of the knowledge and resources needed to start investing in CEFs.

Article Outline:

- How closed-end funds differ from mutual funds and ETFs

- Unique attributes of closed-end funds

- What is included in fund distributions

- A deeper dive into return of capital

- Rules for buying closed-end funds

- The risks associated with closed-end funds

Your introduction to closed-end funds

Closed-end funds are the lesser-known cousins of the mutual funds you know and love. You see, there are two different categories of mutual funds: open-end funds and closed-end funds. Open-end funds are the typical mutual fund you are familiar with in your 401k. Closed-end funds are a tiny portion of the market so they don’t garner many headlines. The Closed-End Fund Center currently shows 638 total funds managing $250 billion in assets. Closed-end funds are geared towards investors that want current income so the majority are bond funds. There are equity closed-end funds as well. The equity funds cover the entire spectrum of stock investment choices. A good way to find what you are looking for is to run a fund screener at cefconnect.com. It will look like this:

What are the differences between closed-end funds, open-end mutual funds, and ETFs?

On one hand, CEFs are similar to both open-end mutual funds and ETFs. They invest in a basket of underlying securities (Apple, Microsoft, etc) and they create units that individual investors can buy. From that foundation, though, the three ‘investment wrappers’ diverge.

Open-end funds trade at the end of the day at their net asset value (NAV). If you add up all of the fund’s underlying holdings and divide by the number of outstanding units, you get NAV. This is your typical mutual fund like Vanguard 500 Index Fund Investor Shares (VFINX). The fund will then redeem or create however many units are needed based on investor buying and selling. The key point here is that you are transacting directly with the fund company at the end of each day.

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) trade throughout the day at NAV. They have ‘market makers’, which are financial institutions that will create new units of ETFs to close any gap between price and NAV. There might be extremely small (0.1%) discounts or premiums, but the market makers will profit from the gap through arbitrage and tighten it down before it gets too large. The ETF alternative to VFINX is the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO).

Closed-end funds trade throughout the day like ETFs but they don’t have market makers so their prices will be at a larger premium or discount to NAV. They also don’t change the number of units available like an open-end fund does. Their price is set by supply and demand; investors buying and selling. The NAV (the value of the assets) is completely independent of the fund’s price (what you pay for those assets).

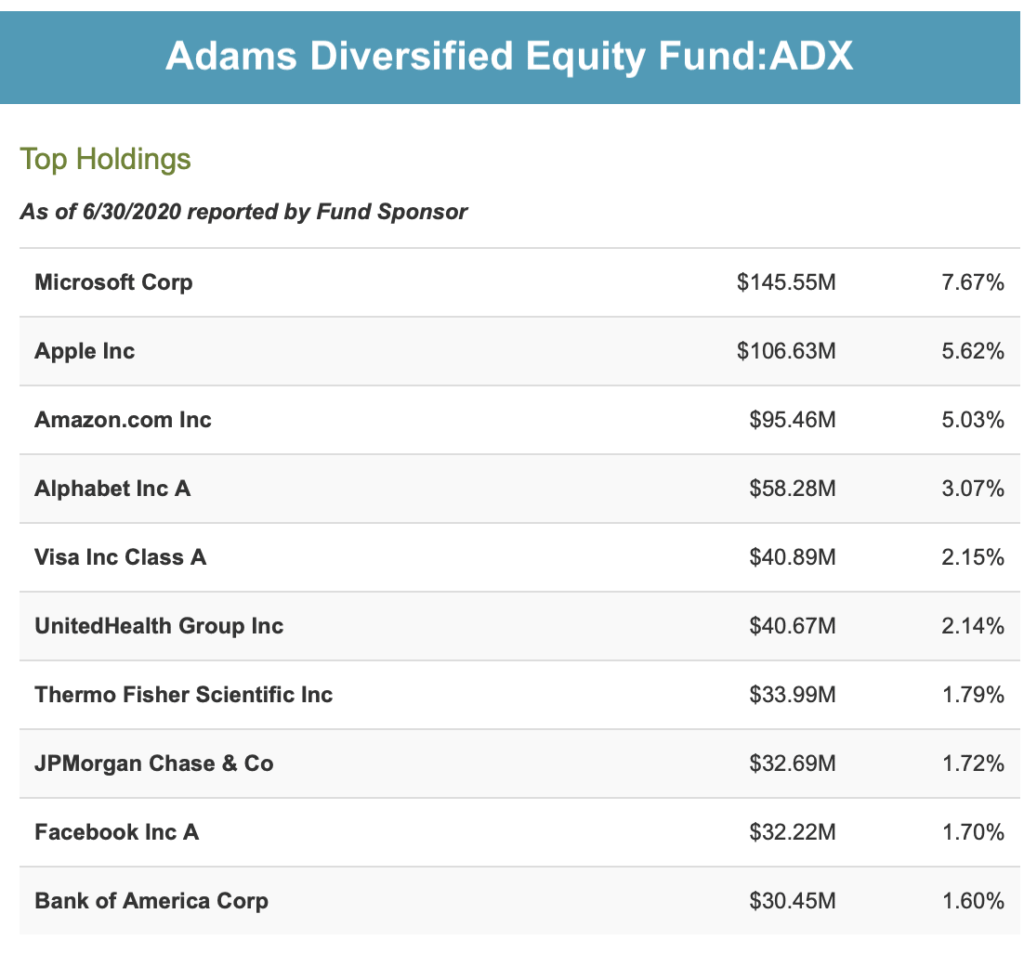

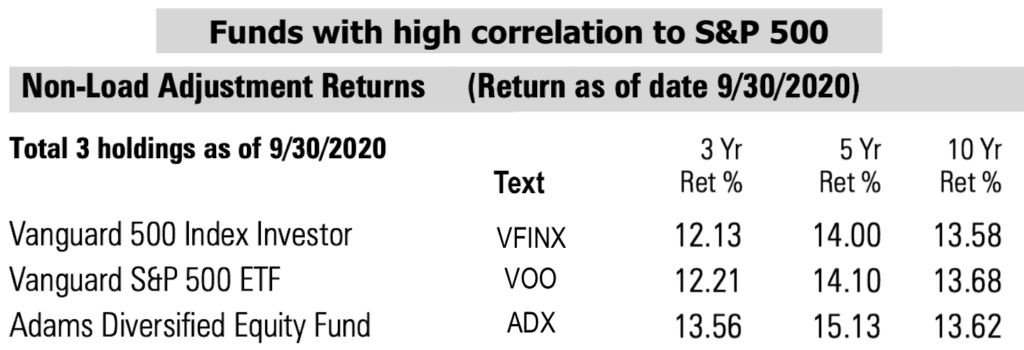

Adams Diversified Equity Fund (ADX) would be similar to an S&P 500 index fund with a 0.99 correlation. It’s professionally managed but the top holdings will look familiar: Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Google, Visa, United Health, Thermo Fisher, JPMorgan Chase, Facebook, and Bank of America.

Closed-end funds and ETFs

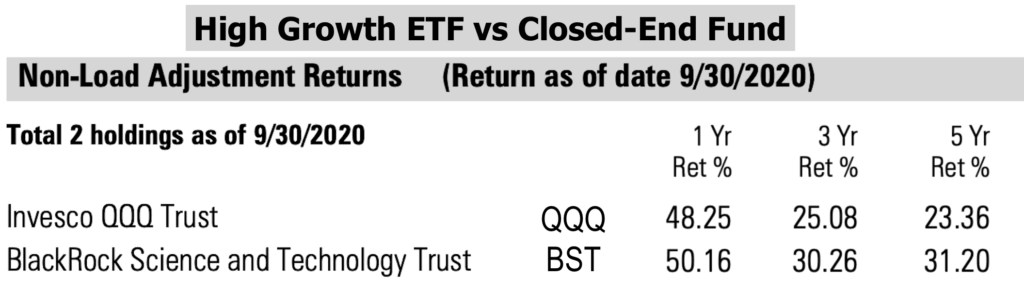

I’m a fan of ETFs. They perform the same function as open-end mutual funds (passive investing) with better characteristics (lower expenses, tax efficiency, and they trade throughout the day). I liken equity closed-end funds to an actively-managed ETF. That may be overly simplified since CEFs have a lot of nuances but here’s an example of what I mean:

The closed-end fund BlackRock Science and Technology Trust (BST) has holdings that look very similar to the popular ETF Invesco Nasdaq 100 Trust (QQQ): Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Google, Mastercard, Visa, Twilio, and Shopify. It also throws in the best Chinese stocks: Alibaba and Tencent. While QQQ’s 23.36% average return over the last 5 years is impressive (as of September 30, 2020), BST has beaten it handily by averaging 30.26% over the same period.

What makes closed-end funds good investments?

To figure out what makes an investment good, you first have to see what makes it different. Here are some unique attributes of CEFs that may make them good investments:

- Professional management that doesn’t have to worry about investor redemptions

- Smart use of leverage

- No cash drag

- Immediate exposure to assets

- Liquidity

- Premium and discounts can be used to further an investor’s profits.

Active Management in a closed-end fund is superior

Manager performance is very important for a closed-end fund because as an investor, you are buying into the fund’s strategy AND the implementation of that strategy.

If the fund is using return of capital early in the year anticipating long-term capital gains, you need to be confident they are right. Otherwise, at the end of the year, those distributions will become destructive return of capital: you are getting your own money back after paying their fees. (we’ll get into return of capital in much more detail later in the article)

A closed-end fund manager has more flexibility when it comes to distributions. They are not just going to pass along the dividends and interest that the fund has received. They can give you extra income from unrealized gains. They can give you the distribution now without having to sell the stocks if they think the stock will keep going up. It will be temporarily listed as return of capital. Let’s say the stock continues to go up for 6 months before the managers sell before the year-end. That leads to improved performance for the fund and turns the temporary return of capital into capital gains (hopefully they also delayed selling long enough to make it long-term capital gains).

This flexibility allows most closed-end funds to pay out an even monthly distribution which is for retirement planning.

Closed-end fund managers don’t have to sell securities to meet redemptions like open-end funds do, hence the ‘closed’ nature of the fund structure. Without having to worry about short-term redemptions, CEF managers can invest with a longer-term strategy and be able to stick to it.

CEF’s smaller size allows them to be nimble when making changes. A multi-billion dollar mutual fund will have to phase out a holding over a long period to not affect the underlying holding’s price.

An example: Vanguard Info Tech ETF (VGT) has $41.5 billion in assets. Apple is 21.88% of its holdings; in other words, this fund holds over $9 billion worth of Apple stock. If it tried to sell all of its Apple stock in one day, that would be an extra 78.4 million shares of Apple hitting the market or about 45% higher volume than normal. They would have to plan out selling their Apple holdings to not affect the stock price. The opposite is also true – the fund would have to phase in a large purchase of stock.

Smart use of leverage

Most, but not all, closed-end funds use leverage to juice their returns and income. They can borrow at very low rates and then reinvest those funds in higher-yielding assets. This is part of the way CEFs can provide higher income than similar mutual funds or ETFs.

Think of it like having margin on your account without the chance of margin maintenance calls.

Closed-end funds list their distribution rates net of fees which includes the interest on leverage. One of the common arguments is their high fees but most of that fee is the interest expense on the leverage. If you are buying at a discount like you should be, the fee is essentially free. Remember, you could be receiving a 7% income rate after fees.

Just like any other kind of leverage, though, it does lead to larger losses in downturns. If you invest, you must think the markets will go up over time so leverage generally leads to alpha. Just keep it in the back of your mind: when stuff hits the fan, high leverage rates will increase losses if you sell.

No cash drag

As we discussed earlier, mutual funds have to handle redemptions from investors. They need to have cash on hand to give to an investor that wants to sell their shares. Otherwise, they have to sell the underlying securities to raise the cash needed for the investor. During normal times, the fund will just keep some cash on hand (about 1% of the fund’s total assets) to handle these daily transactions.

That cash creates something called a cash drag, though. Only 99% of an S&P 500 fund will be invested in the index. The other 1% will be in cash. Even if the fund had zero management fees, its return would still fall behind the index because of the cash drag.

Since closed-end funds don’t have to handle investor redemptions, they don’t have to constantly keep cash on file and don’t suffer from cash drag.

Immediate exposure to assets

When you purchase an open-end mutual fund you don’t get exposure to those assets until after the markets close that day. You gain immediate exposure to the assets because closed-end funds are bought and sold throughout the day. Most of the time this will be a minor issue but there will be times it makes a difference.

Picture a 9/11 situation. A terrible, tragic, major event happens early in the day. You know airlines are getting grounded but you don’t know how much other economic damage will be done. Would you rather be able to exit those securities right then or wait until the end of the day? If you sell your mutual fund you are still exposed all day long to those airlines, or whatever other industry, is going through the shock.

Maybe you don’t have any exposure to airlines and want to wait until the airline prices are in the gutter before buying in. In this situation, mutual funds, ETFs, and closed-end funds exposed to airlines will all experience steep price drops. For mutual funds and ETFs, that lower price will equal its NAV. CEF prices, though, will show a huge discount to its NAV. This allows you to get even more value from the purchase. Why not buy those same assets for 80 cents on the dollar?

Liquidity

Liquidity refers to how easily you can convert your investment into cash. Your bank account is as liquid as you can get since it’s already in cash. Your home is illiquid since it could take months to sell and receive the cash.

Stocks are generally considered liquid. You enter a trade online and the cash is deposited into your account. It might not be the price you want but there is still liquidity.

Bonds, on the other hand, are a grey area. Under normal circumstances, you ask for bids on your bond and generally can sell it close to market value. There are times, usually the worst possible times, that you won’t receive any bids for your individual bonds. At that point, your bond is illiquid and you’ll have to look to sell something else in your portfolio to raise cash. This is exactly what happened during the covid crash of March 2020.

Private equity and hedge funds usually have lockup periods that make them illiquid as well.

Mutual funds, ETFs, and CEFs are all considered liquid but that becomes questionable for mutual funds during the worst of times. As we discussed earlier, mutual funds handle their redemptions directly. They will be forced to sell underlying holdings if they don’t have enough cash to handle redemptions. If they own those same bonds or other illiquid securities they might not be able to sell them when they need to. That will be a very ugly situation for both the fund managers and investors.

Closed-end funds do not have that liquidity issue because investors buy and sell between themselves; there’s no reason to sell the underlying illiquid positions. Instead, the price will be much lower than its net asset value (a big discount). Of course, you won’t like the lower price but it’s far better than not being able to sell your investment at all. This also leads to a huge opportunity with closed-end funds…

Premiums and discounts allow you to take advantage of other investors panicking

Let’s expand on that previous thought: if someone has mostly illiquid assets, like individual bonds during a market panic, closed-end funds might be the only thing available for them to sell.

Other investors looking for a deal will be willing to buy his closed-end funds but since they know he’s desperate to be selling during the panic, they’re going to offer a price way below NAV. As those huge discount windows open up, you can use that to your advantage!

A closed-end fund that normally has a 10% discount may have a 30% discount during these times. You get to buy those assets for 70 cents on the dollar simply because other investors are panicking. Even if the fund’s NAV doesn’t change, you’ll still profit as its discount window slowly goes back to its normal range.

This knowledge can also help you as a holder of closed-end funds. You’ll know ahead of time to expect these price drops and huge discounts opening up on the funds you own. This will help you stay level-headed while others are panicking.

Fixed Income Advantages

About 2/3s of the closed-end fund universe is focused on fixed-income securities. That makes sense since CEFs provide a boost to income and fixed income investors are looking for more income!

Active management is better than passive indexes when it comes to the bond market.

First, market-cap weighting for an index is perfectly fine for equity. As a company becomes more valuable, its market cap goes up and its share of the index goes up to reflect that. Perfect.

On the debt side, though, the index wouldn’t reward the company being smart with its debt; it would reward the company taking on more debt whether it was smart or not. Normally, companies with too much debt are not good investments but a bond index will give you more exposure to those companies. As far as that passive index is concerned, there’s no difference between a company smartly issuing bonds to expand operations versus a struggling company issuing debt just to keep the lights on.

Secondly, the bond markets are not as efficient as the equity markets. This allows active fund managers to get great deals on bonds.

Lastly, the best active fund managers get access to the best new bond issues. The first calls made are to the fund managers at Nuveen and Blackrock, among a few others. They are getting the best bonds being offered that individual investors will never see.

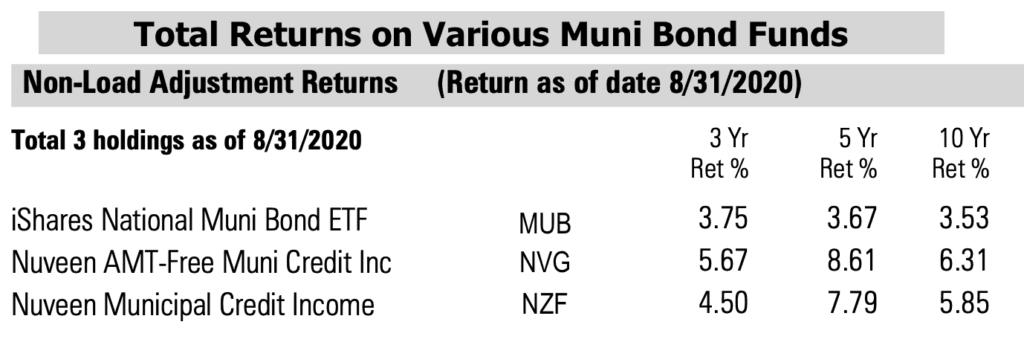

Let’s compare a few funds from each ‘investment wrapper’. iShares National Muni Bond ETF (MUB) has over $17 billion in net assets but has been beaten handily by two Nuveen funds.

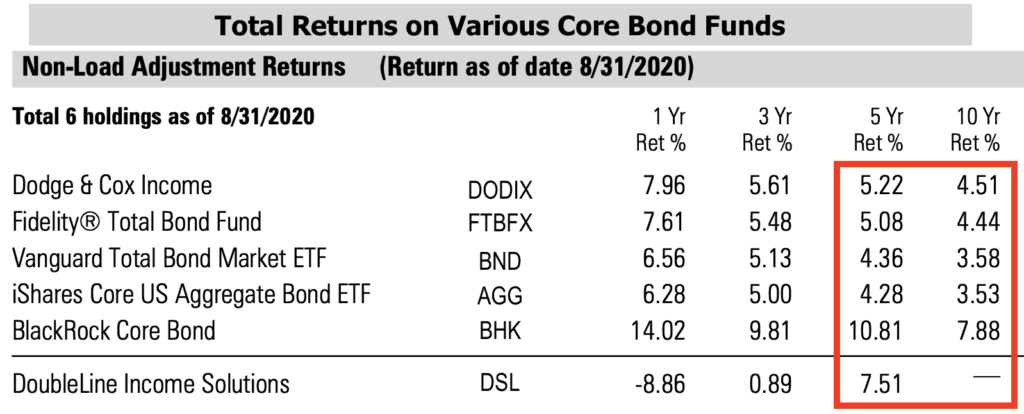

Looking at core bond holdings – some of the most popular mutual fund and ETF funds are listed below, along with a couple of closed-end funds. Again, the closed-end funds show outperformance by a few percentage points a year!

Why settle for AGG or MUB averaging 3.53% a year over the last ten years when you can make 7.88% or 6.31% with the same asset exposure?

How do distributions work?

Most of a closed-end fund’s return is going to be in the form of its distribution. It could have a 10% total return, which includes an 8% distribution. That means only 2% of the return is going to reflect in the fund’s price. Some investors miss that point when they look at their gains and don’t see a closed-end fund going up as much as other funds; they aren’t accounting for the distributions piling up in their cash holdings. It’s still part of its total return even though it’s not reflected in the fund’s price.

Alternatively, you will see some funds with an 8% distribution and 2% total returns – how does that happen? The fund is slowly losing money while paying out the distribution. Done over a long time will cannibalize the fund.

To avoid that situation, you must understand the elements of the distribution.

First, here’s how the distribution is calculated.

A CEF’s distribution rate is based on its price. A $0.825 distribution on a $15 NAV = 5.5%. That’s what the fund managers are earning on the underlying securities. But you get to purchase those assets at a discount. A 10% discount to NAV puts its price at $13.50. $0.825 on the $13.50 you paid = 6.11% yield for you.

A premium would put the distribution at much greater risk: Let’s say the same CEF is selling for a 20% premium. For you to receive the same 6.11% yield (on the new price of $18), the fund would have to produce 7.33% on its NAV. That’s a much more difficult goal than the manager only needing to match 5.5% in NAV.

What might lead to a large discount?

How are some of the most common reasons for large discounts on a closed-end fund:

- Consistently bad returns. Just like any other investment, investors won’t hang around if a fund is losing money year-after-year.

- An unsustainable distribution rate that leads to destructive return of capital and a fund cannibalizing itself.

- A change to distribution policy. Income investors love the consistent monthly income most CEFs provide. If a fund changes its distribution policy, perhaps going to quarterly payouts instead of monthly, that could send investors to the exits.

- Portfolio management: Does the portfolio manager have a good reputation? Heck, is he famous like Jeffrey Gundlach (Doubleline Funds) or Pimco’s Bill Gross? Monikers like “the bond king” and “the bond god” definitely help with a fund’s perception in the marketplace. On the other hand, poor performance by the management team or a change to the management team will have investors paying very close attention to future moves.

- A fund could see a growing discount simply because the investment strategy isn’t currently popular. Picture a value fund after growth has trounced value for many years.

- It could also be from investors overselling or general market volatility. This is the best type of large discount because it’s temporary and you can profit from it!

Next, what are the income sources of the distribution?

The closed-end fund structure gives its portfolio managers more flexibility in how distributions are handled so it’s important as an investor to understand those sources.

Closed-end funds can distribute income from the following sources:

- Interest,

- Dividends,

- Realized capital gains (long and short-term), and

- Return of capital.

The first three sources listed are pretty standard payouts and are handled just like an open-end mutual fund, or an ETF, would handle them.

The safest distributions are dividends and interest because they are the most consistent and reliable forms of income.

Realized capital gains are safe as well, but not as consistent and reliable based on market swings.

Return of capital needs to be analyzed to see what the exact source is. Destructive return of capital should be avoided. Just go to the next fund!

If there is one thing that will separate you from novice investors when it comes to CEF investing, it’s understanding the makeup of a fund’s distribution. In particular, recognizing if any return of capital is destructive.

There are several different types of return of capital:

- Unrealized capital gains, also known as constructive return of capital,

- Pass-through income like from an MLP that issues a K-1 or income from selling options, and

- Destructive return of capital, which is the fund returning your own money to you (net of fees, of course).

ROC is estimated during the year, and finalized at year-end, for tax purposes.

Because these distinctions are so important, let’s dive a little deeper into return of capital.

Return of Capital

Closed-end funds pride themselves on paying out consistent monthly distributions to their investors. After distributing its income, dividends, and realized capital gains for the month, a fund may come up a little short in their distribution from time-to-time, so they will issue return of capital rather than lower the distribution temporarily. A fund’s price will be disproportionately affected by a change in the distribution rate so a little return of capital is a much better option in the fund manager’s eyes. CEF investors like consistent income and will punish a fund that doesn’t honor that. This is fine if it’s done occasionally but a big red flag if it’s abused and becomes a regular part of their distribution.

Now that you know why a fund will issue return of capital, let’s discuss the different types of ROC so you know whether it’s a fund to stay away from or not. As a reminder, the sources of return of capital are constructive, pass-through, and destructive.

Constructive return of capital is only a temporary thing. It’s unrealized capital gains – a fund has a big gain in one of its holdings and it starts giving you the money from that gain before it sells the holding. That money paid out is considered return of capital until the capital gain is realized (the holding is sold and the gain is locked in). Once it’s realized, it’s no longer considered return of capital. Fund management is very important when it comes to unrealized gains because if it’s not done right, the unrealized capital gains are never realized and the payout stays as return of capital. Not good, but still not the end of the world. Keep reading to see when return of capital should have you concerned.

Unrealized capital gains can cause issues during down markets. A lot of funds ‘got caught’ at the end of 2018. They were paying out distributions earlier in the year from unrealized capital gains. The managers planned on selling the securities later in the year, and then the market tanked in December causing all of the unrealized gains to disappear. Since the distributions had already been paid out there was nothing left to do except lock-in that portion of the distribution as a destructive return of capital!

Pass-through return of capital is just an accounting issue and doesn’t mean anything bad. Funds that focus on MLP companies or other partnerships that issue K-1s have to list the income from them as pass-through. For accounting purposes, closed-end funds have to list pass-through income as an investor getting their investment back and hence end up in the return of capital bucket.

There is a positive here, though – you can have exposure to MLPs without the K-1 nightmare that CPAs hate!

Income from selling options will also show up as pass-through return of capital. If you are invested in a buy-write fund you should expect part of your distributions to show up as return of capital. The Eaton Vance Tax-Managed Buy-Write Strategy Fund (EXD) would be a good example. This fund buys shares of stock and then writes call options against those shares. It’s also known as a covered call strategy. In EXD’s case, it allows the fund to pump its distribution rate up to 9.44%! Income from selling options isn’t the same as just getting your own money back so you shouldn’t worry about this form of ROC.

The constructive and pass-through types of return of capital are adding value to the fund, but due to how things are defined in the Investment Company Act of 1940, that’s how they are listed to this day! Most novices will see a return of capital and automatically think it’s bad, but there’s just one type of ROC to look out for…

Destructive return of capital

Destructive return of capital adds no value to the fund. It’s the fund manager giving you part of your original investment back. Of course, that’s done after they’ve charged their fee!

There are two main ways a fund will end up with destructive ROC: not estimating unrealized capital gains correctly or setting an artificially high distribution rate that can’t be sustained.

It’s forgivable if a fund miscalculates its unrealized gains every once in a while. Again, think of the end of 2018. It’s hard to avoid getting caught in that situation. What you should look out for is a fund that consistently screws up this forecasting.

A fund paying out an artificially high distribution rate should be avoided. It is using up its NAV to give you your money back after charging fees. Once a fund starts down this path it’s nearly impossible to recover; its NAV will go to zero. There are plenty of other investments out there so don’t bother with a fund using this desperate strategy!

The easiest way to find destructive return of capital

Here’s the easiest way to see if a fund’s distribution includes destructive ROC: at the end of the year, if its distribution includes any ROC, look at its beginning of year NAV (not price) and end-of-year NAV. If it ended the year lower, the ROC is destructive. If its NAV is higher at the end of the year, it can’t have destructive return of capital.

Example: $15 beginning of year NAV, distributes $2 of return of capital during the year, and ends the year at $14.50. $0.50 is destructive return of capital. You now need to evaluate if this was a rare occurrence or standard operating procedure for the fund.

Most likely it’s because of bad forecasting on unrealized capital gains. If it’s a rare misstep, the fund could still be solid. Take a better look at the management team to see if they deserve your trust.

The other reason is if the managers chose to have an artificially high distribution rate that the fund can’t sustain. My general rule is to avoid any fund that distributes destructive ROC year after year.

A fund’s distribution notice, commonly listed as a 19A report, is a good place to look for the fund’s distribution breakdown (example 1, example 2).

Remember, ROC is only estimated throughout the year and is not finalized until after the year is over. ROC that consists of unrealized capital gains could entirely disappear when you receive the 1099-Div for the fund.

With all that said, though, figuring out the type of return of capital the fund is distributing throughout the yearis tough. You should expect ROC if it is an MLP fund, REIT fund, or has an options strategy built into it. Unrealized capital gains listed temporarily as ROC will be resolved at the end of the year. You can look at past years’ distributions as a guide to see if they are abusing ROC or not correctly estimating their unrealized capital gains regularly.

One bonus of return of capital: it lowers your cost basis, which effectively defers the taxes on that income until you sell the fund. At that point, you’ll have to claim a larger capital gains tax (or a smaller loss). It’s still better to 1) delay taxes, and 2) pay capital gains rather than ordinary income taxes on those distributions.

Here’s an example. You have a cost basis of $15 in fund ABC. ABC distributes $3 during the year, $1 of which is return of capital. You will pay taxes on $2 of the distribution, and then have your cost basis lowered to $14 to account for the $1 of return of capital. Effectively, you didn’t pay taxes on a third of the income you received! That 1/3 will be deferred and converted to long-term capital gains rather than ordinary income. That’s a pretty good deal as long as you know the sources of your ROC.

How do you buy closed-end funds?

The act of buying closed-end funds is straightforward. They are registered securities sold on the stock market exchanges just like ETFs and mutual funds. You type in the ticker symbol, the amount you want to buy, and the type of order (market order or limit order). The more important aspect is knowing which CEFs you should be purchasing and when they should be purchased.

What should you look for when buying closed-end funds?

Just like any other investment, you first need to see how it fits in your portfolio. Does the fund’s strategy fit into your strategy? Will the fund keep your asset allocation where you want it? Is it giving you exposure to the asset classes you want? This is very basic due diligence that should be done for every investment you are adding to your portfolio.

From that base assessment, we can now get into the specific attributes that make for good closed-end fund purchases. Others might add to, subtract from, or just completely disagree with the following rules but I have found them to serve my clients well over the years.

Sources of distributions

We spent a lot of time in this article articulating the various sources of income a fund can distribute. It’s an important factor when determining if you should invest in a fund!

Interest, dividends, and realized capital gains are all good to go.

The only thing to look for is if a fund distributes income labeled “return of capital”. If you see ROC, you need to determine if it’s destructive. Remember the easy way: if the fund’s NAV is higher at the end of the year than at the beginning, it’s not destructive. The return of capital it shows must be either constructive or pass-through if the NAV has increased.

Rule #1: Pass on any fund that consistently includes destructive return of capital in its distributions.

Premiums and Discounts

As explained earlier, a closed-end fund’s price is set by investor trading and can vary greatly from its net asset value. This leads to closed-end funds having discounts (when its price is lower than the NAV) or premiums (price higher than NAV).

A closed-end fund trading at a discount is advantageous in a couple of ways. One, it’s easier for the fund to manage its distribution rate, and two, it gives the investor a chance to buy the underlying assets for 80 or 90 cents on the dollar.

Some CEFs have a consistent discount and there’s not much to gain from that except a higher yield. A fund with assets producing 5% of income being sold at a 20% discount equals a 6.25% yield for yourself.

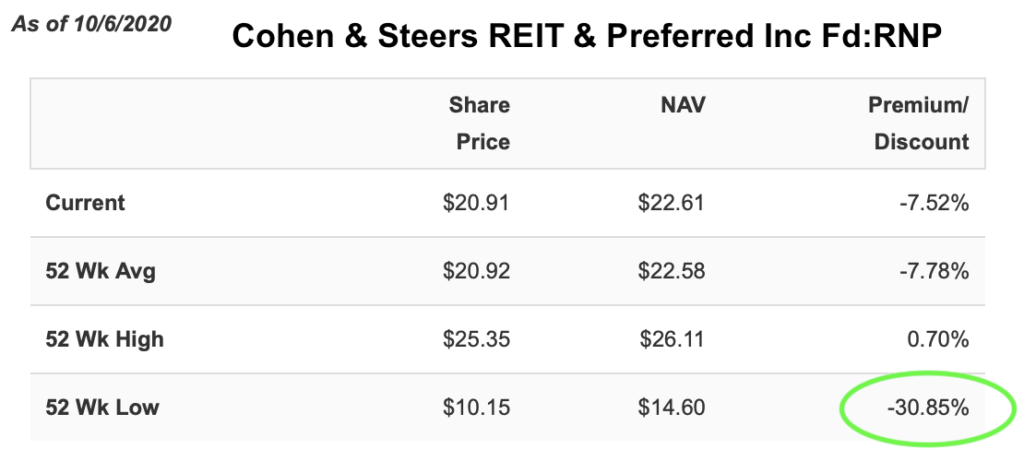

Some CEFs, though, change discount and premiums dramatically and good money can be made buying during those extreme changes. Take a look at the chart below for Cohen & Steers REIT & Preferred Income Fund (RNP). Over this past year, it has averaged a discount of 7.78% but there was an opportunity to purchase the assets at a 30.85% discount! There was even a point where it sold at a premium.

This is a perfect example of how to make money by paying attention to a fund’s discount history.

Rule #2: For a margin of safety, purchase funds selling at a 10% or greater discount.

Rule #3: Compare its current discount to its historical discount to see if greater capital gains can be realized if the discount reverts to its normal range.

NAV performance

While the discount information will tell you if it might be a good time to buy, a fund’s NAV history will show you if it’s a solid fund to invest in. Why the difference? The price is investor sentiment; do they believe in the fund’s strategy and management? It’s NAV, though, will tell you whether the managers have been successful with their strategy despite what other investors think.

The net asset value shows how well a fund’s investments are doing. The fund’s price could drop 10% just because investors panic but its NAV might not drop at all. In that case, you should ignore the price change or see it as a buying opportunity rather than a reason to dump the fund.

Rule #4: Look at a fund’s NAV performance history to see if the fund managers have successfully implemented their strategy.

Rule #5: If a fund has a sudden price drop, see if the NAV showed the same drop in value or if it held its own.

Manager History

Closed-end funds are actively managed, and the ‘closed’ nature of CEFs lets those managers follow longer-term investment strategies than a typical open-end fund manager. That means you have to be very sure that the management team is going to do what they set out to do.

You want to see a management team that has been in place since fund inception or at least more than 5 years. That’s long enough to show if they are capable of meeting the fund’s goals.

You can also look for a fund manager with a legendary reputation. Think Mario Gabelli, Jeffrey Gundlach, or Daniel Ivascyn. They’ve already proven they have what it takes.

What you want to look out for are funds that just started up or funds that switched management teams recently. There may not be anything wrong with them but there’s no reason for you to risk your hard-earned money on them without some history to base your decision on.

Rule #6: Look for manager longevity and reputation. You need to trust them for the long-term investment strategy.

Understand the Tax Qualities of the Fund

This rule is pretty straightforward – know the tax qualities of the fund so you know which type of account you should hold it in. If you want to buy a tax-free municipal bond fund like NVG, it should be purchased in a taxable brokerage account. If you are looking to purchase muni’s in an IRA, you should look for higher-yielding taxable municipals from a fund like BBN.

Rule #7: Match the fund’s tax qualities to the type of account you are purchasing it in.

Review the quick and easy rules

Rule #1: Pass on any fund that consistently includes destructive return of capital in its distributions.

Rule #2: For a margin of safety, purchase funds selling at a 10% or greater discount.

Rule #3: Compare its current discount to its historical discount to see if greater capital gains can be realized if the discount reverts to its normal range.

Rule #4: Look at a fund’s NAV performance history to see if the fund managers have successfully implemented their strategy.

Rule #5: If a fund has a sudden price drop, see if the NAV showed the same drop in value or if it held its own.

Rule #6: Look for manager longevity and reputation. You need to trust them for the long-term investment strategy.

Rule #7: Match the fund’s tax qualities to the type of account you are purchasing it in.

Following these rules should keep you out of too much trouble in CEF land. As is the case with any investment, you’ll develop and refine your parameters as you gain investment experience with closed-end funds.

Risks

1. They do sell off big when s*** hits the fan, even muni bond funds. Why? It’s the only liquid thing to sell. You literally can’t get bids on small lot individual bonds during those times so you have to unload the CEFs.

2. Most CEFs don’t have a ton of trading volume each day so you need to be a little more careful when entering trades. Always use limit orders! The funds are liquid so you are guaranteed a trade. A limit order guarantees the price.

3. If you buy a CEF at a high premium (which you shouldn’t if you made it this far into the article!), that can put a real strain on the fund to distribute that amount of income and the fund can end up cannibalizing itself.

4. Leverage risk: most, but not all, CEFs utilize leverage to boost their income and returns. It’s usually a smart move because they can borrow at very cheap rates. Like borrowing on margin in your account, though, when the markets tank the leverage will lead to larger losses.

5. If the fund produces all of its returns through income to you (8% distribution rate and an 8% total return), then after a big market drop, it might continue giving the same income but since that’s its entire return you’ll never see the price appreciate back to where it was.

Investors and advisors who don’t really know CEF’s will point out two items that aren’t deal-breakers:

- CEFs are too expensive! CEFs can indeed have expense ratios in the 2-3% range, but most of that expense is the interest on the leverage. Paying an extra 1% for leverage could earn you an extra 2-3% in return. Also, remember that the distributions are quoted NET OF FEES. The fund could be giving you 7% in income AFTER the fee has already been deducted. Finally, factor in the 10-20% discount you paid for the assets, and the fee is practically comped.

- Return of capital is too dangerous! Return of capital can be dangerous but we’ve thoroughly discussed what to look for regarding ROC and how to avoid the destructive kind.

Conclusion:

Closed-end funds occupy a very interesting corner of the investment world that most people don’t know exists. Now that you do, you can see how they might fit into your portfolio. This is especially true as you start the distribution phase of your portfolio. Don’t be a sucker settling for 2% yields on treasuries. You can easily be collecting 6% even in our current zero percent environment. You don’t even need to make your portfolio complicated. Here’s how to incorporate closed-end funds into a “3 fund portfolio”.

*Disclosures: This article is for information purposes only and should not be considered individualized advice to act upon. The investments mentioned in this article are used to fit certain examples and are not specific recommendations. Each person should do their own due diligence for any investment or strategy they implement.