Googling the topic of inherited IRAs brings up a lot of articles outlining the new rules. There is very little outlining the best way to approach the withdrawals, though. This article rectifies that with the easy “Years Remaining” strategy that will maximize the amount of the beneficiary IRA you get to keep in the long-run.

What happened?

The SECURE Act changed how long non-spouse beneficiaries of IRAs have to withdraw the money and it makes a big difference in your retirement planning. The SECURE act stands for Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement. (Congress loves their acronyms, don’t they?). It was signed into law on December 20, 2019, and takes effect for any IRA inherited January 1, 2020, or later.

Prior to the SECURE Act, IRA beneficiaries could take advantage of a feature that led to the nickname ‘stretch IRA’. It was referred to as a stretch IRA because you could stretch out the payments over a long time period. They could withdraw a small amount every year for pretty much the rest of their life. (The final balance would have to be withdrawn at the ripe age of 111!) That also meant the taxes could be stretched out over that time period as well!

How does the change affect you?

Well, the government got tired of waiting for those taxes, so under the SECURE Act, IRAs inherited by non-spouse beneficiaries now must be withdrawn over 10 years. This is for any IRA inherited in 2020 going forward and it makes a major difference in your tax planning.

Technically, the withdrawal period is a little longer than ten years because the beneficiary has until December 31 of the 10th year following the IRA owner’s death. Here’s an example: Joe Smith dies on March 1 of 2020. Ten years later will be February 28, 2030. But his beneficiary doesn’t have to withdraw all of the money by this date. They have until the end of the 10th year to wrap things up, December 31, 2030. In this case, the beneficiary has an extra 10 months to work with.

Easy mode: Just visualize the year of death not counting, and then you have 10 full years to complete the withdrawals.

There are a few exceptions (disabled beneficiaries, beneficiaries not more the 10 years younger than the deceased, and minor beneficiaries) so make sure to check with your tax preparer in case you are covered by any of the exceptions.

Luckily, if you inherited an IRA prior to 2020, you get to keep the stretch provision and continue the same payment formula for the rest of their lives.

You inherited an IRA after the SECURE Act went into effect. What are your options?

First, there’s actually one nice feature – you have a lot more flexibility in withdrawing the money. There’s no rigid formula with a 50% penalty if you don’t take out enough each year. You just have to make sure it’s all out by the end of the 10th year! The main issue is that taxes will be higher overall since you have to withdraw the money over a shorter time period.

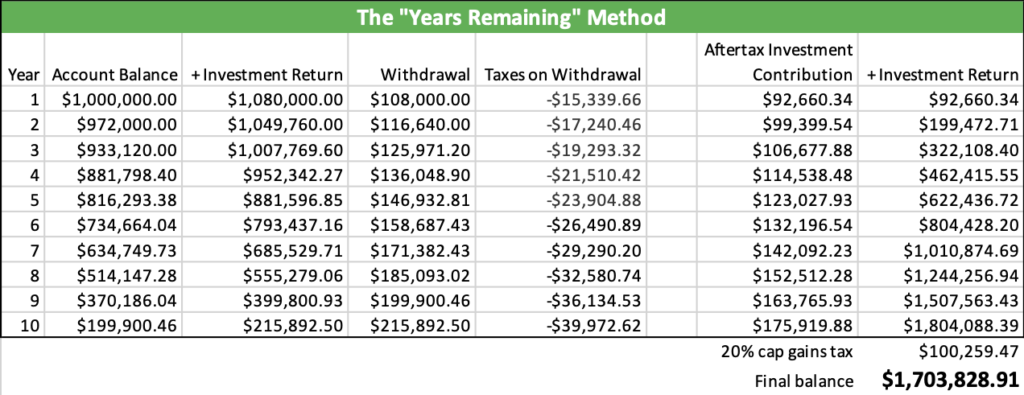

For our different strategies, we’re going to assume you inherit $1,000,000 and the funds earn 8% a year while they are in the inherited IRA. We’ll also assume that once you move the funds out of the IRA, you’ll continue to invest them at 8% in a brokerage account. At the end of the 10 years, we’ll assume you sell everything and have to pay 20% capital gains tax on the earnings in the brokerage account. Unrealistic, I know, but taxes will be owed at some point on the brokerage assets and this allows us to compare apples to apples in the timeframe we’re given. These assumptions will keep our focus on the different amounts of taxes paid based on the timing of the withdrawals.

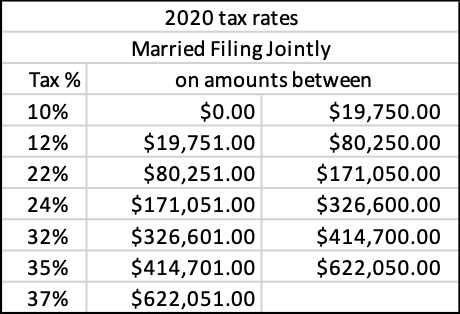

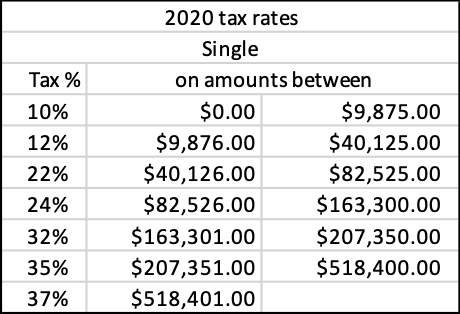

This is the tax structure I used for someone married filing jointly. This doesn’t factor in any outside income or standard deductions. Those variables would be the same no matter which strategy chosen; therefore, they don’t need to be taken into account. Each withdrawal strategy is being exposed to the exact same tax structure:

Here are some of your options, including the easiest, most ideal withdrawal strategy!

So, you’ve inherited an IRA from a loved one. The money might not mean much to you initially but no matter how long the grieving process takes, at some point you will be happy to have it and thankful for the person that left it to you.

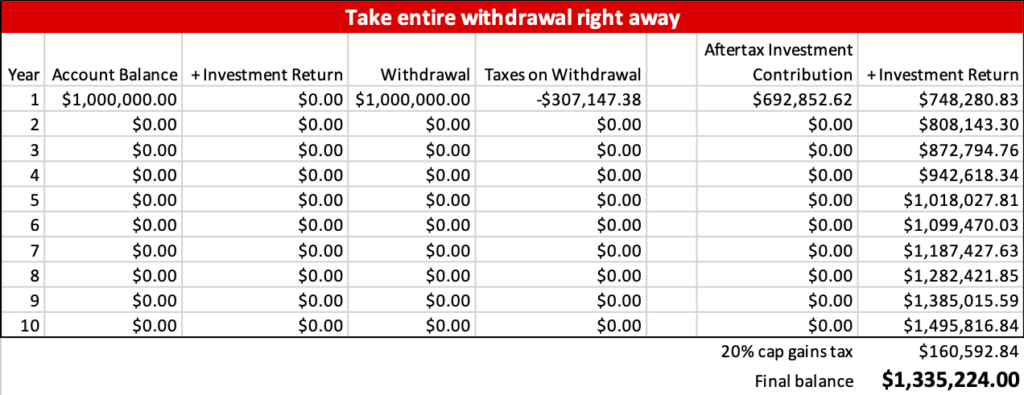

Option 1: Immediate Withdrawal

Your first inclination might be to figure out what will happen if you just take all of the money right away! Well, get ready for the IRS to become your new best friend – you will be paying them $307,147.38 that first year. If you invested the remaining $692,852.62 and earned 8%, you would have $1,495,816.84. Paying 20% capital gains tax on the earnings leaves you with a final balance of $1,335,224. I guess that doesn’t sound too bad, right? Wrong – it’s actually the worst possible outcome. Unless you need every penny of the inheritance for something right away, don’t take out the entire amount right away. (If you do need every penny of the inheritance right away, you seriously need to re-evaluate your financial life!)

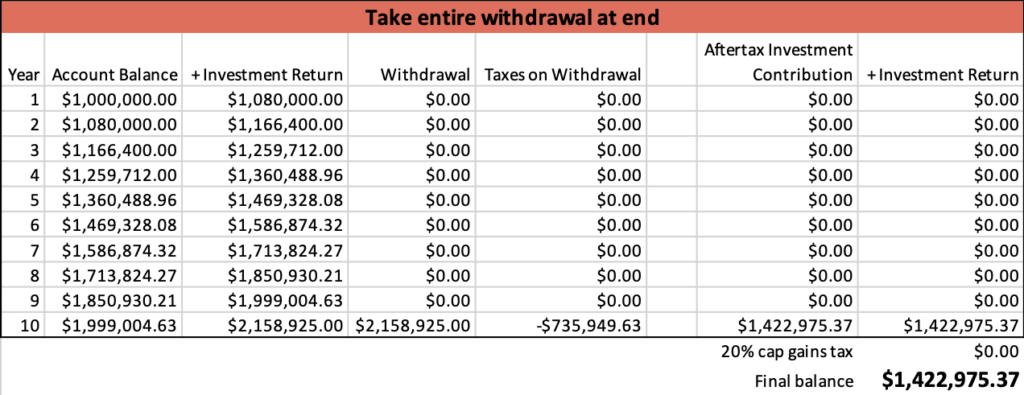

Option 2: Take entire withdrawal at the very end

If taking the withdrawal upfront isn’t ideal, then maybe deferring the taxes for as long as possible is the answer. You get tax-deferred growth for 10 years, and the beneficiary account builds a balance of $2,158,925. Now here is where the pain sets in – you now owe the IRS $735,949.63 in that last year! The IRS loves you! You do get to move the remaining $1,422,975.37 to your after-tax brokerage account, though. Delaying taxes let you collect about $87,000 more than paying the taxes upfront but is it the optimal strategy?

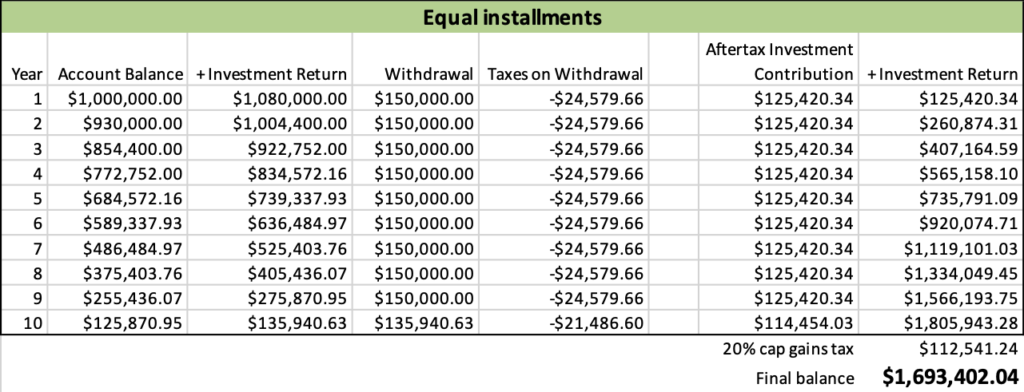

Option 3: Take out an equal amount each year

For this strategy we’re going to spread out the withdrawals as evenly as possible over the entire 10 years. For this strategy to work, you’ll need to estimate how much the account will earn each year in order to know how much to withdraw each year.

Here are some examples:

- If you plan on earning 4% each year, you’ll need to withdraw 12.33% of the original balance each year.

- If you plan on earning 8% each year, you’ll need to withdraw 14.91% of the original balance each year.

- If you plan on earning 12% each year, you’ll need to withdraw 17.7% of the original balance each year.

I’m using the 8% estimate and rounded the withdrawal rate to 15% each year, or $150,000 of the original $1,000,000 balance.

The idea behind this strategy is to expose as much of the withdrawals to the lowest tax brackets each year. The strategy works, too! You’ll end up with $1,693,402.04, or $271,000 more than option 2. Spreading the withdrawals out over all 10 years is definitely the way to go.

Here’s the issue, though: you have to estimate how much the account will earn ahead of time. If you’re wrong, the results won’t be as optimized. They’ll still be better than options 1 or 2, just not optimized.

Option 4: Use the “Years Remaining” method

The numbers make it clear – spreading the withdrawals out is the way to go. But could there be an easier way to spread them out without trying to estimate your investment returns? I figured out an easy way that I call the “Years Remaining” method. All you have to do is remember how many years are left in the 10 year period, and take that fraction of the account out. It doesn’t matter if you take the money out at the beginning of the year or the end of the year. It doesn’t matter if your investment returns change from year to year. It just works.

In the first year, when there are still 10 years left, you will take out 1/10th of your account balance. If there are six years left, you take out 1/6th of the balance. Two years left? Take out ½. And then in the final year you take out the remaining balance (which would happen to be the fraction 1/1).

That’s it! Super easy. The results will have you patting yourself on the back as well – it comes out ahead of option 3 by $10,000.

Another aspect of the “Years Remaining” method I like is it has an inflation-like withdrawal schedule. With positive investment returns, you’ll be taking out a larger withdrawal each year.

Does a different tax situation make a difference?

In the previous examples, I was treating it as if the person had no other income. That allowed the first amount of withdrawals each year to be exposed to the lowest tax brackets. That would obviously favor the latter two options with even withdrawals over all ten years.

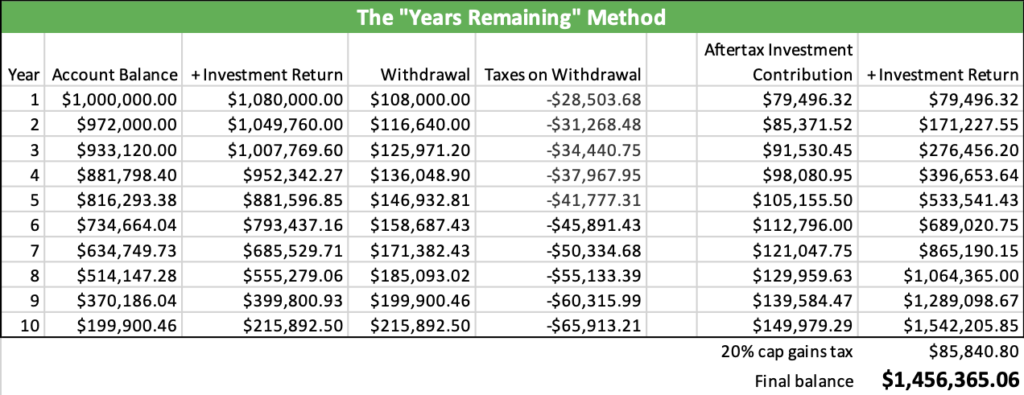

How would the results change if someone was making a good salary already? That means every dollar of the IRA withdrawals was being exposed to higher tax rates. To do that, we’ll take a person making $100,000 a year and filing single. We’ll give them the standard deduction of $12,400. Their W2 income is taking up the first $87,600 of the low tax brackets, and then the IRA withdrawals get put on top of that. 24% is the lowest tax rate the withdrawal money is exposed to in this situation. Does this change the optimal strategy?

Here are the results for our single high-earner:

- Option 1 Immediate withdrawal: $1,249,298.45

- Option 2 Withdraw at end: $1,378,388.29

- Option 3 Even withdrawals: $1,446,938.27

- Option 4 “Years Remaining”: $1,456,365.06

As expected, all of the final amounts are lower due to the higher tax exposure. The order of the results did not change, though! Spreading out the withdrawals still pays off with the “Years Remaining” approach allowing you to have the highest balance.

Does a different return estimate make a difference?

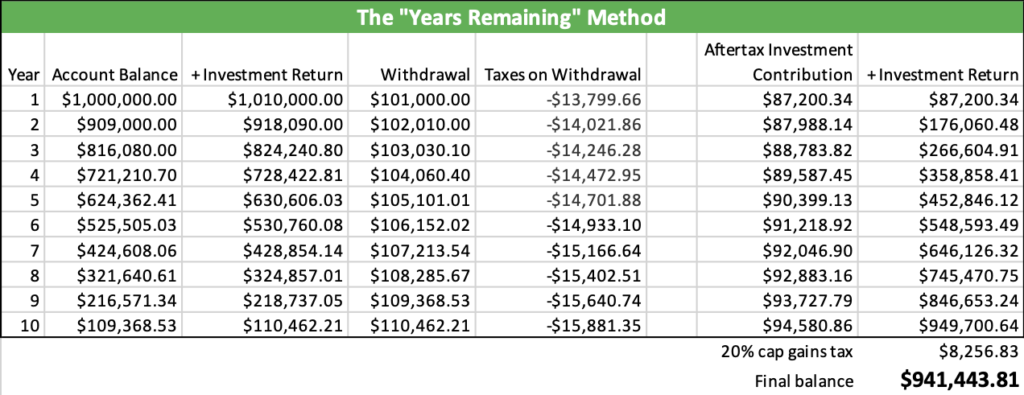

Let’s say you are super-conservative and earn 1% in a CD, money market fund, or even a treasury ETF rather than a stock-bond mix earning 8%. Would a lack of investment returns make a difference? Perhaps if there’s practically no investment returns it won’t matter when you take the money out.

We’ll go back to our original married filing jointly couple and adjust their returns from 8% down to 1%. Everything else stayed the same.

Here are the low-investment-return results:

- Option 1 Immediate withdrawal: $750,842.79

- Option 2 Withdraw at end: $758,764.56

- Option 3 Even withdrawals: $941,279.11

- Option 4 “Years Remaining”: $941,443.81

Even without high returns, there still remains a distinct advantage to spreading the withdrawals out. The “Years Remaining” method still came out on top.

What if you don’t need the money being withdrawn each year?

You are pretty much out of luck. There’s no way to avoid the taxes completely. Qualified charitable distributions are not allowed from inherited IRAs. QCDs allow the money to go directly from the IRA to the charity with no taxes withheld. You won’t get the up-front tax avoidance even if you withdraw the money and donate to charity. Donating to charity may lower your tax bill based on your deductions but that has nothing to do with the inherited IRA. You first have to take the money out of the IRA which triggers the tax liability on the withdrawal.

Some might suggest a Roth conversion on a portion of the inherited IRA but that is not allowed for non-spouse beneficiaries! Only a spouse can do that.

The only way to absolutely avoid the taxes is to disclaim the inheritance before ever receiving it. Just remember that it’s an irrevocable refusal to accept the inheritance. If you go broke the following year, you can’t come back and say, “Oops, my mistake! Please give me the inheritance now”.

Conclusion

It definitely pays to spread out the withdrawals over the entire 10 years. Option 1, taking out the entire balance at the beginning, will leave you with $1,335,224. Option 2, taking out the entire balance at the very end, is a little better with a final balance of $1,422,975. The main difference between the two is letting the tax-deferred growth continue for an extra 10 years.

The trick is to balance your withdrawals fairly evenly over the entire 10 years. This allows the most amount to be exposed to the lowest tax rates each year. Options 3 and 4 show this advantage, with ending balances of $1,693,402 and $1,703,828.

You could have 20% more money at the end of the 10th year if you optimize the withdrawal schedule. Option 4, the “Years Remaining” approach, gives the best results in each situation we covered today. It’s also much easier to implement versus the even withdrawal amounts of option 3. Just keep track of what year you are in and take out that fraction of the account. No up-front estimating needed!

Also remember that different tax brackets and/or different estimated returns didn’t change the results. Spreading out the withdrawals will always beat taking a huge withdrawal in any one year.

No matter which strategy you choose, make sure you are maximizing your investments!